Ahead of its time: Archaeolink Visitor Centre (1997)

Completed in 1997, the Archaeolink Visitor Centre In Aberdeenshire was a radically different kind of building: conceptually, visually, and also in its approach to energy conservation. Twenty-five years on, as architects strive for operational net zero carbon, the project’s innovative passive design has valuable lessons for today…

The Archaeolink Trust, formed in the early 1990s, had a vision to open up northeast Scotland’s ancient archaeological heritage to the public by creating an educational tourist attraction. The Archaeolink Prehistory Park would be located in the Aberdeenshire countryside: a beautiful and historically significant area boasting seven iron age forts set on conical hills, with a backdrop of the Bennachie ridge – a hill whose silhouette was held in Pictish legend to be a sleeping giant.

Cullinan Studio began working with the trust to design a Visitor Centre for the park in 1994. It would provide a starting point for visits, and incorporate an exhibition space relating the story of the region’s archaeology, plus a theatre, education centre, shop and restaurant.

The building, completed three years later, was radically creative in multiple ways.

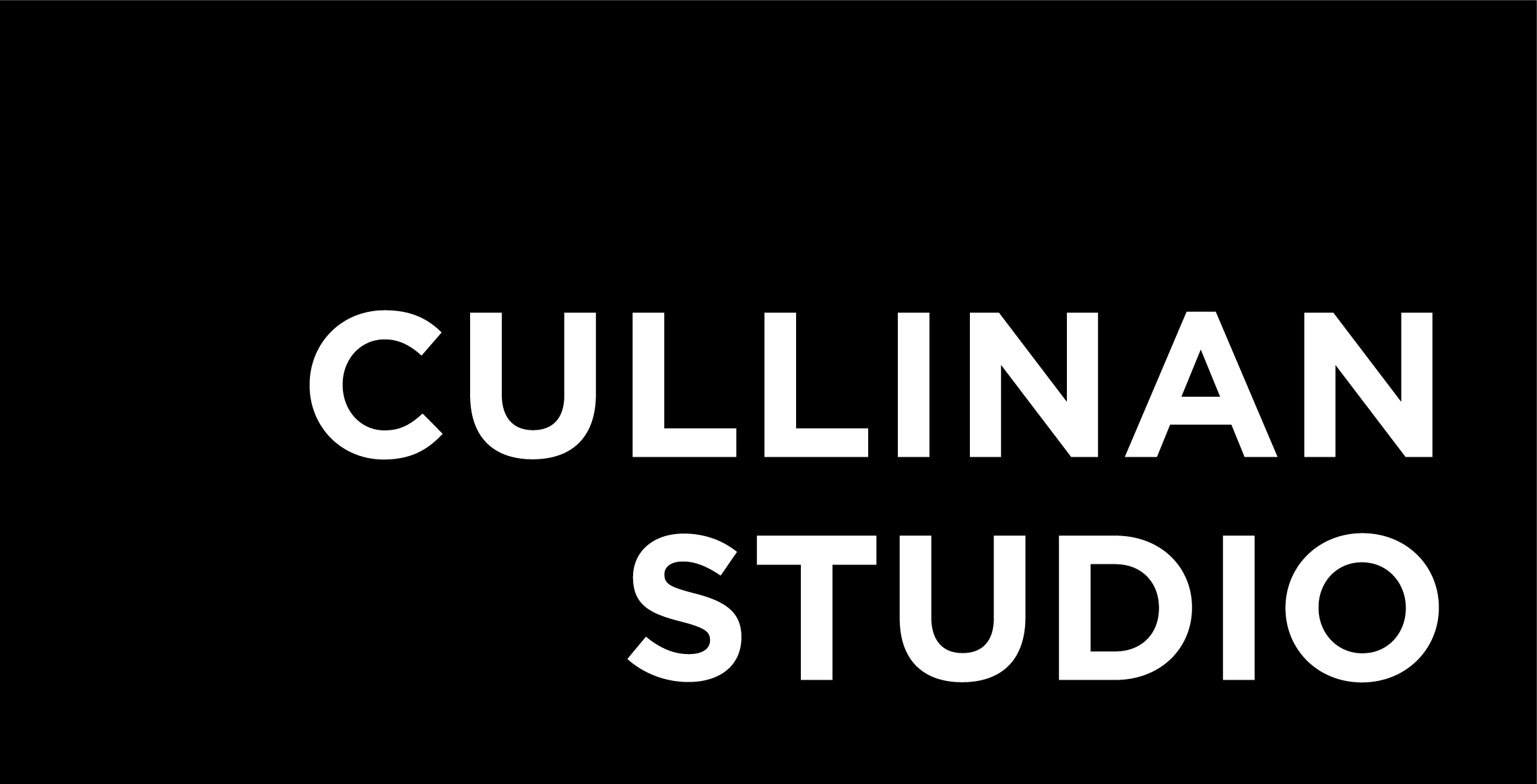

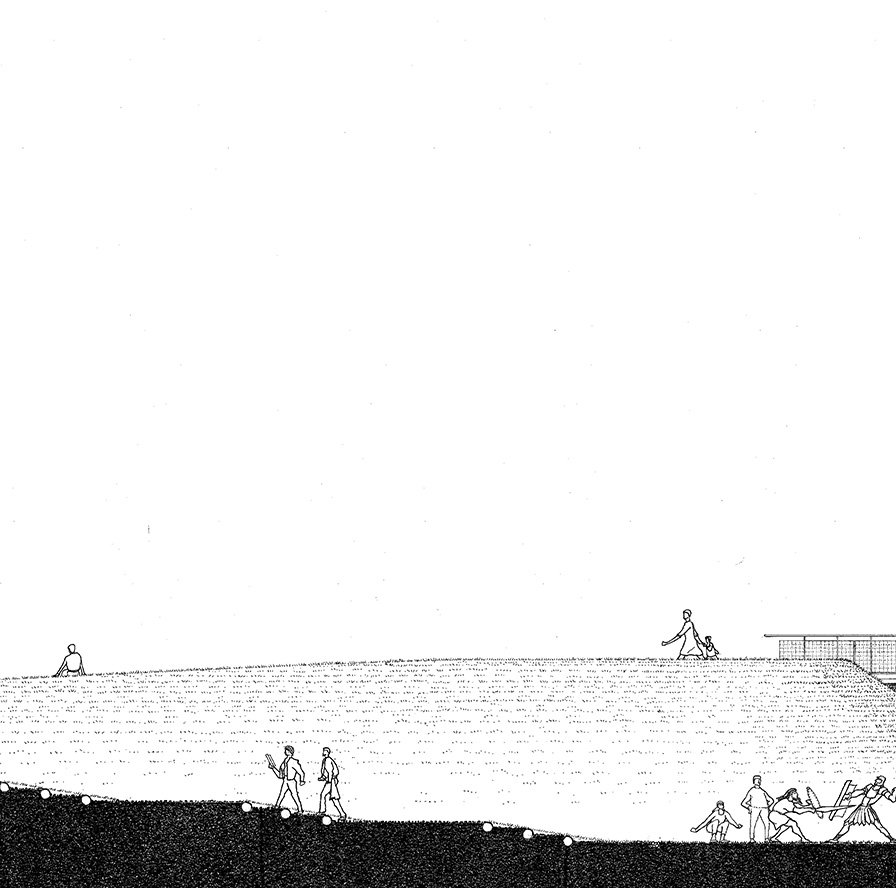

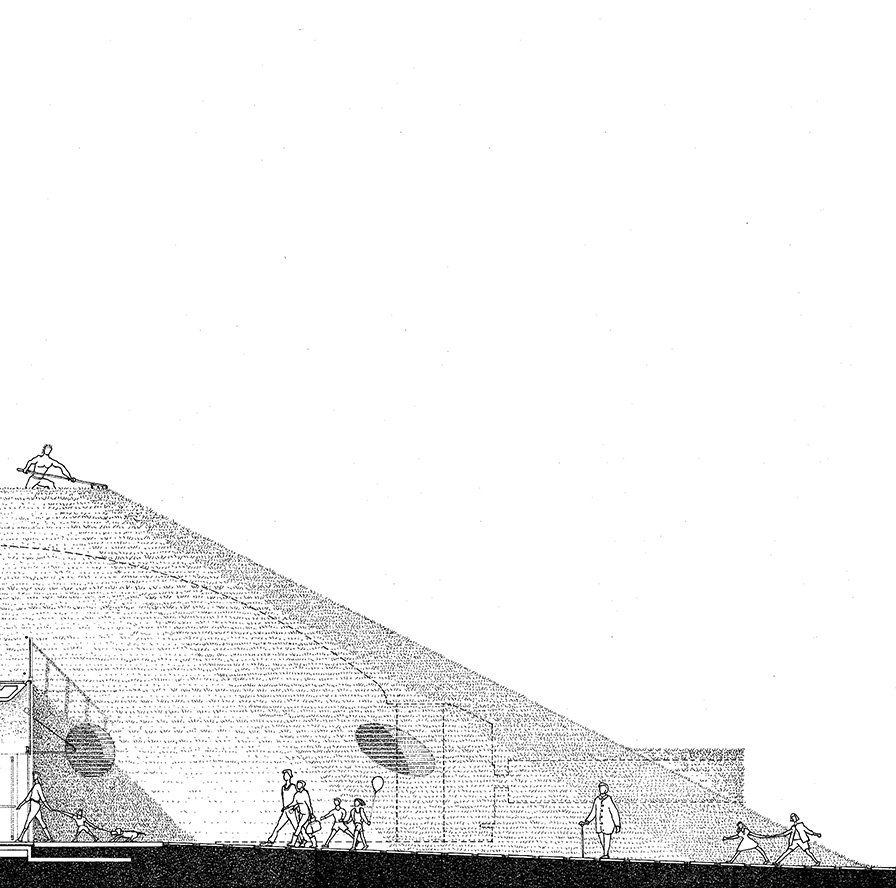

Visually, the Centre melded seamlessly into its rural setting. This was achieved by setting it within incisions in the ground, so that the landscape seemed to roll over it. The roof was grass, rising like one of the conical hills that surrounds the centre, and the land was ‘folded’ to form a sheltered courtyard and valley entrance.

Care was taken so that the setting and layout would actively enhance the visitor’s experience of the area and its landmarks, with one approach walk aligned on the sacred mountain of Bennachie, and another on the view down the Garioch valley to the ruined castle on Dunnideer hill (this technique of carefully creating vistas towards landmarks that add purpose and meaning to the visitors approach was developed on the Fountains Abbey Visitor Centre project).

Inside the Centre, the open layout allowed free circulation to all parts of the centre, with each of the facilities housed within colourful ‘drums’, set like boulders in a stream of visitors looking at indoor and outdoor exhibitions, shopping or eating. Glass walls provided light and views to the restaurant and shop within. Automatically-controlled blue fabric shades limit direct glare from the sun on bright days, while white soffit panels bounce in more light on gloomy days.

As a building made of grass and glass, the Centre was immediately recognised for its innovation and creativity. It received a Scottish Design Awards Commendation for Best New Building, and in 1998 it was announced as one of the Design Council’s ‘Millennium Products’ – the only building out of the 202 items included.

From Prehistory to Passivhaus

However, looking at Archaeolink Visitor Centre a quarter of a century on, one of its most striking and pertinent innovations is its approach to energy efficiency.

Today, finding ways to minimise a building’s energy consumption has become an imperative for architects, as we strive to achieve operational net zero carbon amidst the climate crisis. To operate at net zero, a new building must power its lighting and appliances and regulate its temperature without contributing a positive quantity of carbon emissions in doing so. In practical terms, that means it will need to achieve an energy balance: reducing its heating, cooling and electricity consumption to the point where it can be covered by its own renewable energy production (e.g. via solar panels).

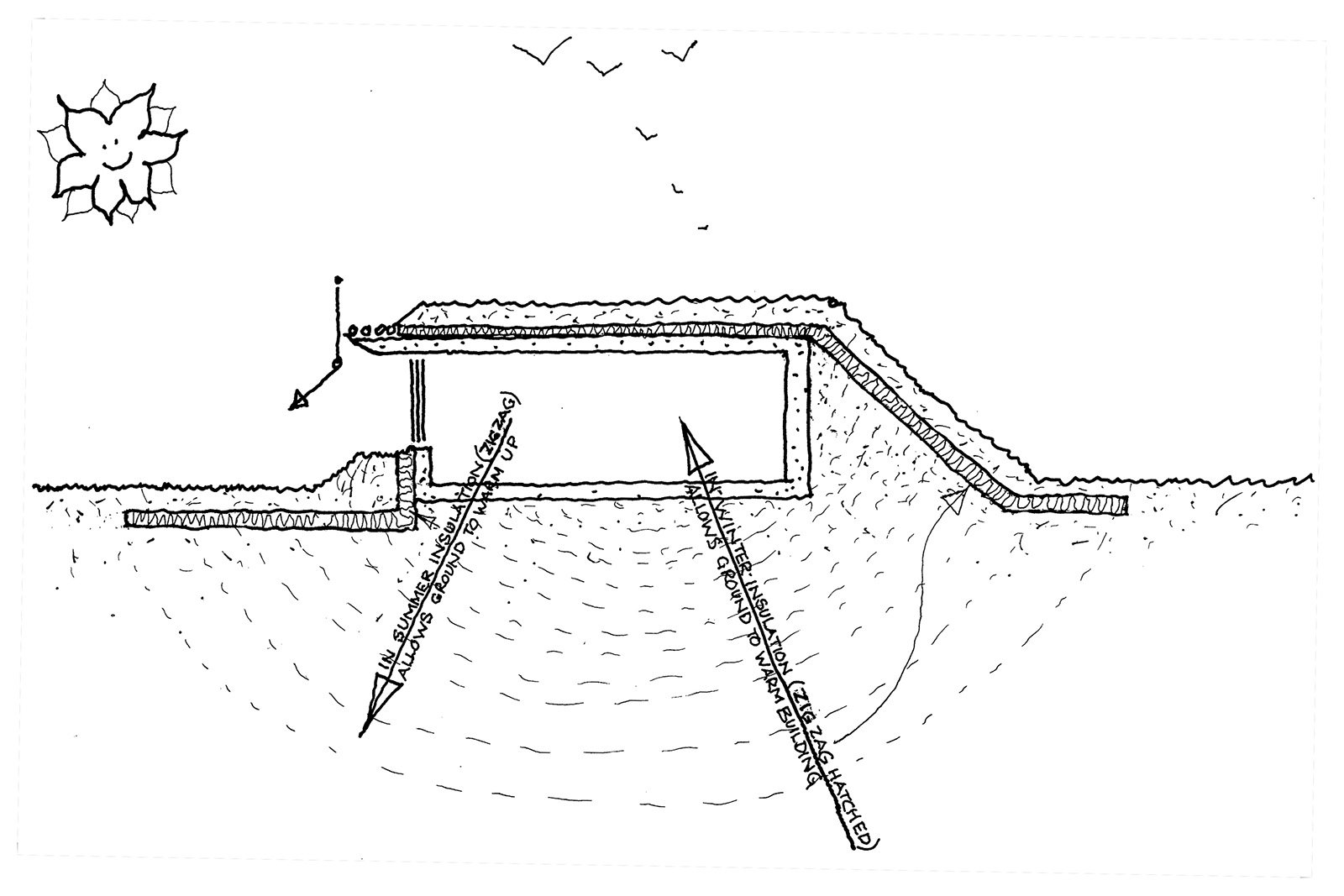

The Archaeolink Visitor Centre was radical in incorporating energy efficiency into the core of its design. It was designed with engineers Fulcrum to need minimal heating in winter, by taking advantage of the large thermal mass of surrounding earth. Much like a cave, it trapped ground heat to achieve a steady temperature state. The concrete structure was exposed throughout, allowing the passage of heat between the Centre and an insulated underground heat store in an annual heat-cool cycle. Heat losses were topped up by solar heat gain via the glass walls.

This form of interseasonal storage followed research by the Rocky Mountain Institute, whereby the cloak of insulation continues across the external ground for 4m beyond the buildings facades. The heat store builds up in summer then gradually depletes over the winter months. It is designed to achieve a baseline temperature of 16 degrees across the year. It therefore used its natural environment to produce and conserve energy and to minimise its demand.

Now when we take on a new project, the contemporary methods and tools we use to reach this energy balance, including Passivhaus principles, inform the design of a building from its earliest stages. What was highly unusual in 1997 is now an essential element of mainstream architecture. In that sense, the Archaeolink Visitor Centre was decades ahead of its time.

What happened to Archaeolink?

The Archaeolink Visitor Centre eventually closed in 2005, after Aberdeenshire Council withdrew supporting funding. Currently unoccupied and awaiting a new use, the landscape has gradually begun to reclaim the building.

Now in our seventh decade, Cullinan Studio have always been innovators; specialists in things that have never been done before. Our blog series Ahead of its Time takes a look at some of the groundbreaking projects from our history, showing how the concepts that shaped them also helped to reshape mainstream thinking about architecture and the way buildings connect to places, people and the natural environment – today and for the future.

If you would like to discuss any of the ideas raised on our blog, contact us.