The Circular Economy, and how architects can help to build it

Architects can help make the concept of the circular economy a reality – but the picture is bigger than simply building efficient, low-waste buildings. Here’s how we can design the circular future…

The circular economy concept seeks to tackle global problems like pollution, biodiversity loss and the climate crisis by changing the way that systems work. It focuses on the elimination of waste: in our current ‘linear’ economy, we take resources from the Earth, make products from them, and then throw them away as waste. But in a circular economy we prevent waste from being produced in the first place.

The circular economy is a powerful and challenging idea to guide how humans might manage their material impact on the environment so that instead of steadily degrading, it continually regenerates. That is how the natural world works. Nothing is thrown away for there is no such place as ‘away’. Any ‘waste’ from natural processes becomes food or fuel for other processes in the cycle of life.

Sunand Prasad – Trustee of UKGBC

The Ellen McArthur Foundation, which leads the way on circular economy thinking, identifies three key principles: (1) Design out waste and pollution; (2) Keep products and materials in use; (3) Regenerate natural systems.

Their ‘butterfly diagram’ illustrates the continuous flow of materials in a circular economy in two main cycles: the technical cycle, in which products and materials are kept in circulation through reuse, repair, remanufacturing and recycling; and the biological cycle, in which the nutrients from biodegradable materials are returned to the Earth to regenerate nature.

But how do architects contribute to the circular economy? Clearly, on the level of individual projects, they can make use of recycled, reclaimed and sustainable materials, design energy-efficient buildings and seek to minimise waste in the construction process. (See: How to design a building on circular economy principles)

But in a properly realised circular economy, buildings and venues cannot exist in isolation. How they function, how they interact with their locations, and how their users interact with them are all vitally important. This is the bigger picture that architects and masterplanners can help to deliver.

Here are five ways that architects can design the circular economy…

1) Provide the vision

One can theorise about a ‘circular city’, where infrastructure, buildings and functions operate on circular economy principles – but what does that actually look like? Architects and masterplanners specialise in taking abstract ideas and visualising them; turning concepts into designs.

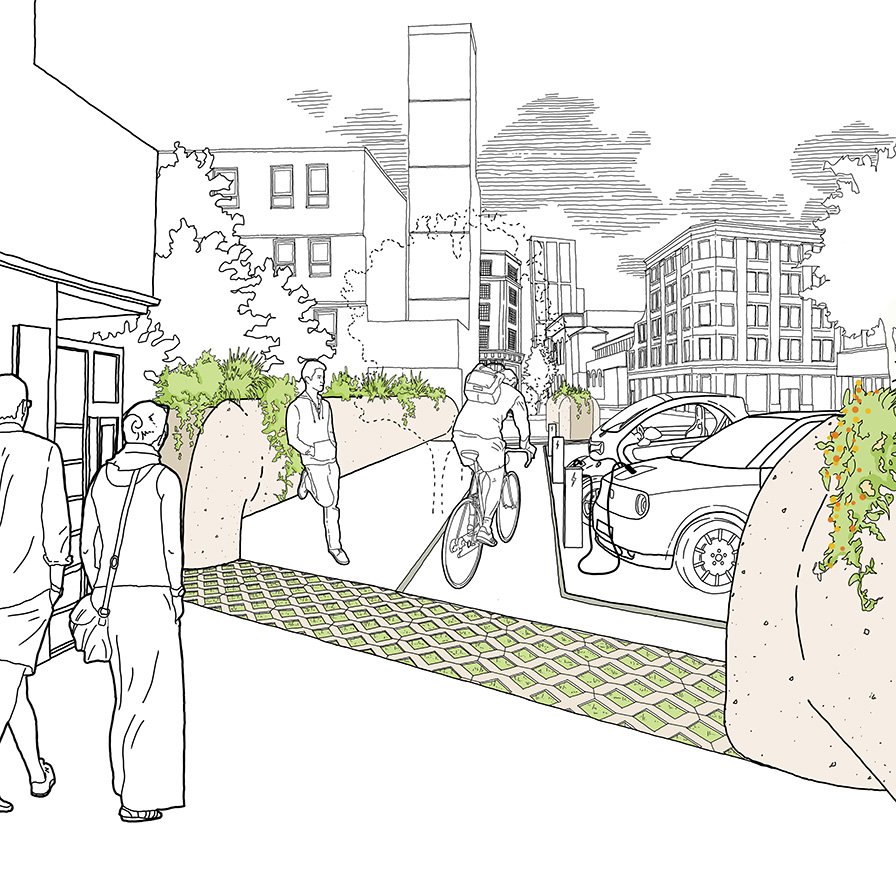

How could a circular cityscape look – or a district or street? Recently Cullinan Studio worked on the pioneering Bunhill 2 Energy Centre in Islington, which uses waste heat from the London Underground to deliver discounted heating and hot water to a neighbouring primary school, two local swimming pools and over 800 local homes. The fan that extracts the heat can be reversed to cool the Tube tunnels in the summer, while technology developed in the project also generates cheap, green electricity that powers the communal lighting and lifts of an adjacent tower block.

These benefits go beyond just district heating and open up possibilities for power and mobility; for low-cost, low-carbon ways for a local area to power its own buildings, applications and even transport: for example, using green energy for electric vehicle charging points.

These are the kinds of circular economy projects that we are working on with our partners in the GreenSCIES project: applying new, circular ways of thinking not just to individual buildings but to districts and their interconnected functions. Cullinan Studio specialise in projects that have never been done before. Turning circular thinking into urban reality will require innovation, creativity and vision.

Visualisation of a heat loop concept, part of the GreenSCIES project.

2) Make connections, foster collaboration

The first principle of circular economy thinking is to design out waste. But it is virtually impossible to create waste-free complex, workable buildings and systems without venturing out of the design studio; without collaborating with the people who will use them. Cullinan Studio projects always include extensive consultation with local communities throughout the design process. These are the people with the knowledge of how to reduce waste and use local resources; who can tell you which features and assets should be preserved or reinvented.

Designing complex circular systems also requires making imaginative connections – and wide collaboration with multiple parties. Designing and building Bunhill 2 meant bringing together parties including civil engineers and specialist District Energy engineers, and needing to meet the various requirements of Islington council, TfL, Planners and local residents. Cullinan Studio’s role was to help facilitate between all these parties, coordinating infrastructure, architecture and the community engagement.

3) See what’s already there

The second key circular economy principle is to keep products and materials in use.

For architects, this means looking to retrofit existing buildings first, reversing the traditional approach of tearing down to build again from scratch. This does not come naturally to all designers: good retrofit requires an ability to understand the building, its location and the intentions of the original architects.

The fundamental principles behind retrofit – the preference for looking first at what is good and useful about an existing building in order to preserve, adapt and reimagine – go right back to the philosophy of our founder, Ted Cullinan. Our own studio is a retrofit and our portfolio contains award-winning retrofits ranging from a 1960s system-built school building, to the Grade II-listed country house that became an office complex and then a retirement village.

The same ways of thinking apply beyond individual buildings and materials – to localities, and to the ways that people live, work and interact with each other within a place.

Cullinan Studio is in the process of designing the new Marlborough Sports Garden according to Circular Economy principles: collaborating with local users, preserving existing structures, using reclaimed and sustainable materials, incorporating nature and designing for long term flexibility.

4) Allow space for nature to thrive

The third principle of the circular economy is to regenerate nature; supporting natural processes and leaving more room for nature to thrive.

For architects this means using natural sustainable materials such as timber wherever possible. But it also means incorporating a connection to nature into all buildings and urban spaces, and allowing wildlife to thrive through green spaces, gardens and natural water features. Encouraging biodiversity is a principle that we carry into all Cullinan Studio projects.

5) Design for the unpredictable

For the circular economy to become a reality, planners must not only understand the past, so that they can reuse and preserve, but also design for the future.

This does not mean predicting exactly how buildings and places will be used decades ahead, but rather making sure that everything we make now is flexible and adaptable to unknown future needs. For example, designing buildings that can have multiple functions, and can be easily and cheaply adapted to different purposes. It also means considering end of life: interiors that can be easily disassembled; modular designs and standard elements that can be reused again and again.

Cullinan Studio is committed to turning the principles of circular economy thinking into architectural reality. If you would like to discuss the issues raised by this article, contact us.