Ahead of its time: the Cullinan Studio model of Employee Ownership

Half a century ago Cullinan Studio pioneered a cooperative, income-sharing partnership model for an architectural practice. Our structure brings challenges but also tremendous benefits – and it is founded on just three elegantly simple principles…

Led by organisations like the Employee Ownership Association, the idea of employee ownership is currently flourishing. There is plenty of evidence that staff are more committed to a business’ success when they are given a financial stake and a role in decision-making; and that co-owned companies tend to be more competitive, profitable and sustainable.

In the field of architecture, Cullinan Studio is known as a pioneer of employee ownership. Our cooperative structure dates back to our foundation over 50 years ago, and is still going strong. Today, many architects see us as an inspiration; and we advise other practices (in architecture and in other fields) on adapting the kinds of cooperative principles that have served us over the decades.

But Cullinan Studio’s set-up remains highly unusual: not just in our particular sector, but even in terms of EO businesses.

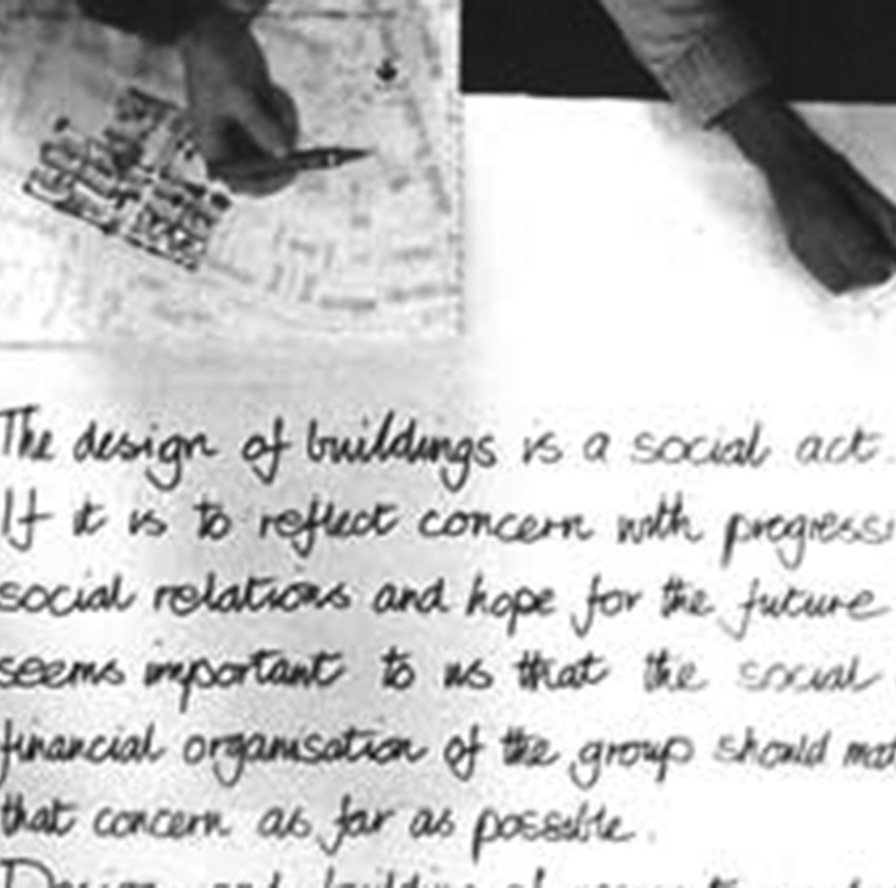

Ted Cullinan’s manifesto: ‘Design and building of necessity involves co-operation’

Five decades ago our founder Ted Cullinan and his seven partners wrote out a manifesto that begins ‘The design of buildings is a social act’. Ted had a vision for a new kind of architecture practice: a co-operative of partners who consciously designed for the society around them, contributing to a sustainable and equitable future.

He believed that ‘design and building of necessity involves cooperation’ and we are still driven by the belief that a building’s potential is maximised when the interests of all stakeholders are engaged with and cohere with the goals of the project.

Ted’s groundbreaking step was to apply this philosophy to the financial and corporate structure of his own practice. The Cullinan Studio conception of a cooperative partnership essentially boils down to three remarkably simple principles, although the details of how these are applied is elastic and has evolved with the changing times and personalities of the partners.

These principles are: (1) income is shared openly and equitably; (2) nobody has buy in or builds up capital; (3) the model must serve the work.

There are tremendous practical benefits to this approach. Our cooperative culture ensures that we are comfortable working in detail and depth with other organisations and professionals, and our cooperative structure ensures our partners are all equally invested in success. We work well with large and diverse teams, with complex organisations and on multi-layered, innovative projects because collaboration is our founding principle.

But there are also challenges for any practice seeking to follow in our footsteps and adopt these principles. To take each in turn…

1) Income is shared openly and equitably

Ted Cullinan’s manifesto states: “Fees are shared in agreed proportions as and where they are received; any surplus is shared out or used otherwise by agreement.”

In the early days when cheques (and presumably bills) came in, the money was literally shared out amongst (or collected from) the partners. Today we have a more complex system but the core principle remains.

Everyone agrees each others’ proportion of the overall salary pot, based on value and experience, with a maximum pay differential of 1:3. The division is negotiated in an annual open meeting. Partners who feel undervalued can make a case for a larger slice, but they will be aware that that is then cut from everyone else. The salary pot is then reassessed each quarter, based on predicted fee income and other outgoings, so that pay rises and falls according to the performance of the business.

There are challenges with this approach: the open meeting can be emotionally difficult; and just as gain is shared equitably, so is pain in difficult times.

But it also means that everyone understands the worth of what they do, and takes collective responsibility for the effect of their decisions on the overall wellbeing of the office.

2) No one has to buy in and no one builds up capital

‘Making the practice have no book value ensures that it is no-one’s possession nor is anyone its servant,’ states the manifesto.

Cullinan Studio’s shares are held in a trust, and if the company is ever dissolved the assets will go to charity. This means that there is no financial barrier to becoming a partner – typically, team members become a partner after about two years.

It also means that any partner who wishes to move on can do so easily. The idea is to build a committed team, with members investing in each other and in making a success of the business. No discontented team members will be ‘hanging around’ waiting for a pay out, and when they do go, there are no difficult transactions of dissolving a partnership or selling back shares.

The prospect of having no capital to show for years of work is not for everyone – and indeed many partners have left over the years. But there are also many who are still here decades on, and there is now a large network of former partners who still feel a bond and are on good terms with the practice.

3) The model must serve the work

‘...the special contributions of eight individuals find best continued expression when the co-operative idea is paramount, supported by shared concern with the quality of the work we do, as well as the will to share it and the money.’

It’s important to note that for Ted Cullinan, the cooperative idea was not an end in itself, but rather a means to achieve high quality architectural work. He insisted that ‘if it stops serving that aim, we’ll do it another way.’

That still holds true to this day. Our cooperative principles must serve our purpose to create healthy, environmentally sustainable buildings that connect to nature and to their communities; and our corporate structure must support a financially viable business operation that allows us to continue working.

Inevitably, the details of our cooperative partnership have evolved and will continue to do so, as times change and the particular custodians of Cullinan Studio come and go.

But fundamentally, we still have a cooperative partnership model to this day because it still serves our purpose. It works.

For more information about Cullinan Studio’s conception of employee ownership and a cooperative partnership structure, and for advice about implementing some of our principles in your own practice, contact us.